The profits generated from UK agriculture fell by a quarter in 2015 compared with the previous year, with some farms losing considerably more than others.

Estimates for 2016 suggest a muted recovery, specifically in the second half of the year, after sterling weakened relative to the euro. For 2017 so far, prices and markets suggest that the year is likely to be more profitable again, based on current market values, crop and stock conditions.

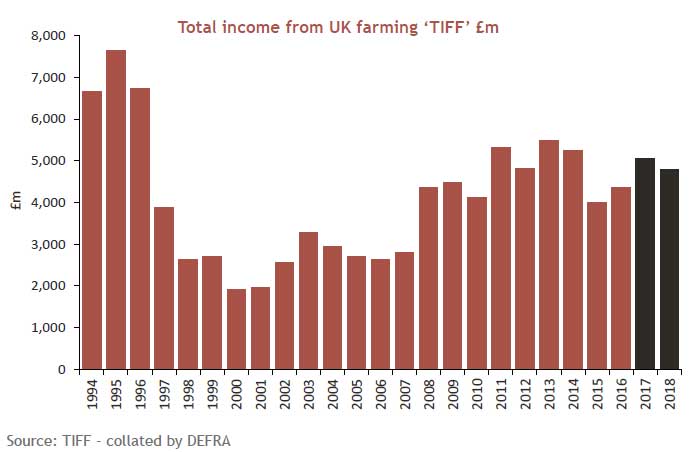

Total Income From Farming (or TIFF) is a useful measure to look at the UK farming industry as a whole, providing a simple measure of the profit of ‘UK agriculture’. In technical terms, TIFF shows the aggregated return to all farmers in UK agriculture and horticulture for their management, labour and their own capital in their businesses.

Examining TIFF in real terms over the long term puts the 2015 decline into perspective as, only seven years earlier, did the industry come to the end of a 10-year period of considerably poorer farming conditions. Whilst difficult, that period made the industry more efficient, stronger and resilient.

The EU’s Basic Payment subsidy is calculated in euros then converted into sterling using the average monthly exchange rate for September each year. The 2016 Basic Payment was about 19% better than 2015 because of a more favourable exchange rate. Volumes of output (e.g. milk and cereals) actually fell in 2016 compared with 2015. As it currently stands, profits for 2017 could return to the levels seen in 2011 to 2014, driven by the weaker pound and brisk sales of agricultural commodities since June 2016, where agricultural stocks have been keenly sold to European buyers.

In fact, commodities, by definition, are priced at the point of sale (or close to it if they are sold with a supply contract). Wheat, for example, can vary in price several times throughout a single day. This led to a sharp rise in the value of agricultural outputs since the European referendum in June 2016 (wheat is worth roughly £20 per tonne more and milk about 2.5ppl more).

This rise is an immediate sign of inflation. Farm inputs are mostly products and services. These categories of goods tend to have fixed prices over a longer period of time than commodities: Agrochemical prices are usually adjusted seasonally, wages tend to change annually and other costs such as rents might be reviewed less often than that. In other words, agricultural inputs are generally slower to respond to inflationary pressures than outputs.

This suggests that farm outputs have already benefitted from the decline of sterling, but the costs (assuming sterling remains more or less where it is) will be rising now. We could therefore conclude that, unless agricultural markets fundamentally move up again, the UK farm profitability will fall in 2018.

The nature of commodities and farming means that farmers are largely ‘price takers’. Careful cost control can be the key to maximising profits in fluctuating market conditions.

Where incomes and profits swing from one year to the next, the introduction of 5-year farmers’

averaging will help to smooth the results and the tax liabilities due.

DISCLAIMER

By necessity, this briefing can only provide a short overview and it is essential to seek professional advice before applying the contents of this article. This briefing does not constitute advice nor a recommendation relating to the acquisition or disposal of investments. No responsibility can be taken for any loss arising from action taken or refrained from on the basis of this publication. Details correct at time of writing.

Disclaimer

This article was previously published on Smith & Williamson prior to the launch of Evelyn Partners.