Equity markets have been frustratingly defiant to everyone sitting on the side-lines waiting for a correction. The argument for caution is that high equity market valuations at a point where interest rates are poised to rise is a dangerous combination in anybody’s language. Unfortunately for these investors, and happily for everyone else, there have been limited opportunities to take advantage of any market weakness or schadenfreude so far this year.

Global growth is encouraging

The MSCI World is up 8.3% in local currency terms and 5.3% in GBP. Easy monetary policy has continued to dominate, fiscal spending has been neutral to positive and, post a 50% fall in the Bloomberg Commodity Index from 2012 to 2016, the relative stability of commodity prices has encouraged a return of emerging market capital flows and global growth.

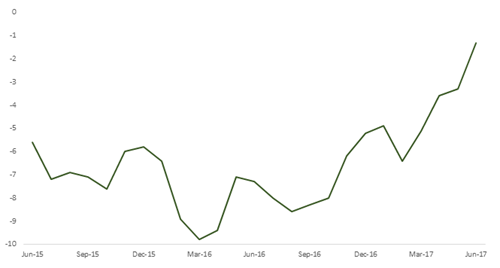

We have been particularly encouraged by the resumption of earnings growth in Europe and the improvement in consumer confidence in the region (see graph below). The rise of populism also appears to have moderated.

EU consumer confidence

Source: Lipper

Confidence is key

Confidence is extremely important for investors. On average, the change in valuation accounts for about 60% of the market return in any single year and consumer confidence is a crucial factor behind it. If consumer confidence is rising, investors are less likely to be disappointed by earnings, and valuations will directly reflect that increasing level of certainty.

A fall in unemployment has clearly helped confidence in the EU and the resulting rise in total income and consumption raises the probability for better earnings. The recent bank bailouts in Italy and Spain are also a positive for growth, reflecting a recognition and partial resolution of the outstanding non-performing loans that have stifled European growth over the past eight years.

What’s next for interest rates?

Of course, the question now is whether the European Central Bank (ECB) and fellow Central banks around the world are in the position to decide that growth is strong enough to turn off the liquidity tap and start the long road back to a “neutral” interest rate.

The Federal Reserve (Fed) has already begun raising rates but easy monetary policy elsewhere has made these increases largely ineffective. Long-term yields remain stubbornly low and yield curves are relatively flat.

The need for coordinated action

A coordinated increase is a pre-condition for yield curves to move higher across the maturity spectrum, and would be far more effective than the Fed acting in isolation. We have seen a little of that recently when Carney, Draghi and Yellen appeared to simultaneously become a little more hawkish in late June. The spread between German and US 10-year bond yields has since narrowed, and the euro has sprung into life as a result.

If this coordinated tightening were to persist, it would give the cash-rich investor something to smile about at last, since equities will pause for thought. The euro has appreciated nearly 8% year to date against the US dollar and Europe’s exporters are already beginning to complain.

Preparing for the next downturn

The textbook argument for raising interest rates put forward by Janet Yellen and the governors at the Federal Reserve is that they need to anticipate inflation and be in a position to lower rates to stimulate growth during the next cyclical downturn. Perversely, getting rates back to normal may actually be the cause of the recession but the objective is to not be left with quantitative easing as the only arrow available next time around.

Low US unemployment

Unemployment in the US at 4.67% is currently well below the normal level of full employment, and it is quite understandable that the Fed fears that a “hockey stick” shift in wage inflation is just around the corner. Given the lags of monetary policy, we can see the logic behind a move in interest rates up to neutral (around 1.5-2%) in a relatively short timeframe.

However, in our view it is still unlikely that policy at the Bank of England, the ECB or the Bank of Japan (BoJ) is going to change materially in the same timeframe. And without that coordination, long-term interest rates in the US are likely to continue to be anchored at low levels.

China boosts global growth and commodity prices

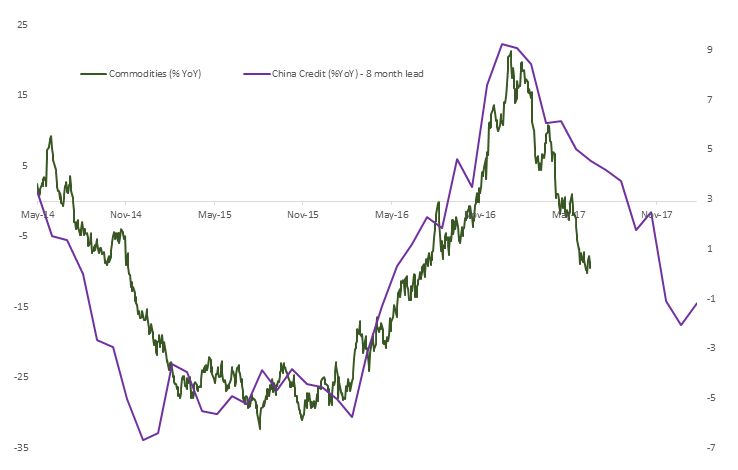

Our reasoning behind this dovish view starts on the other side of the world in China, where credit and fiscal expansion have helped the authorities hit their growth targets with boring precision. Fiscal spending grew by 3.5% of GDP in 2016, and in the same time period the change in broad credit creation moved up from -5% year on year in 2015 to +10% year on year by mid-2016.

In combination, these changes catalysed a powerful stimulus to global growth toward the end of last year and into 2017. With a lag of around eight months, the credit impulse drove a welcome recovery in commodity prices and a broad rebound in global growth, particularly in the commodity dependent emerging markets (see graph below) – hence the strong performance of emerging market equities.

China credit impulse and commodities

Source: Lipper

Most casual observers probably credit the recovery in oil prices to the OPEC output agreement in November 2016. However, the low in the oil price actually occurred nine months before that meeting and almost exactly eight months after credit growth started to increase in China. The data suggest – rather surprisingly – that the price of oil is set in Beijing rather than Riyadh.

We expect a slowdown

Since August 2016 the credit impulse in China has slowed quite dramatically and during 2017, the fiscal deficit will increase only fractionally suggesting that the peak in the current wave of global activity has passed – and taking account of the lag effect, we can expect global GDP growth to slow in the second half of the year.

China is now the second largest economy in the world at US$11.5 trillion in GDP, and probably growing at twice the rate of the USA (the numbers are a little unreliable!) A change in Chinese growth today will impact the world economy, and to misuse a meteorological metaphor, the wings of the Chinese butterfly are now flapping at a slower pace. The slowdown expected in China also coincides with a decline in loan and credit activity in the US, which again points to the potential of a negative growth surprise in the US over the next few months. Both indicators suggest an upward inflection in early 2018.

Consistent inflation will continue to elude Central bankers

The second reason for our dovish view is that, apart from in the UK, Central bankers targeting inflation have probably seen the headline numbers peak this year due to negative year-over-year commodity price comparisons. The green shoots of inflation have been music to the deflated ears of the ECB and BoJ, but we fear that consistent inflation will elude them a little longer. As a result, while both may tighten marginally from current extremes, they are likely to remain extremely accommodative.

Yellen will defer further interest-rate increases

With this backdrop in mind it is possible that the Federal Reserve will make a policy mistake and raise rates into a temporary slowdown that emanates from China. This loss of momentum could be viewed quite negatively by equity investors who are already struggling to find value in an expensive market.

It is possible that the Republicans finally get something done on tax reform to ameliorate investor concerns. But in our view it is probably more likely that Janet Yellen will identify the risks and defer further increases in interest rates to the beginning of 2018 or at least the December 2017 meeting. Mario Draghi may also feel confident enough to signal an end to the bond buying programme in Europe fairly soon, but Europe is not out of the woods yet, and the overall policy stance would remain supportive of growth and risk assets like equities.

What’s next for the UK and sterling?

In the UK, it is a blessing for our UK equity managers that around two thirds of FTSE 100 earnings come from outside the UK, and that the currency has improved the terms of trade for exporters. The disastrous leadership skills of Theresa May combined with the Brexit negotiations have probably been enough to deter any material fixed asset investment into the UK for quite some time.

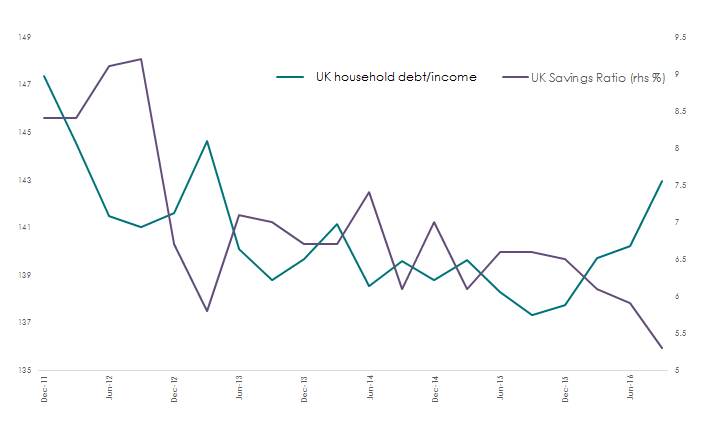

What also concerns us is the apparent debt-fuelled consumption binge (see graph below) and lack of any improvement in the UK’s trade balance by value as the appetite for imports continues unabated.

UK consumer balance sheet

Source: Lipper

Clearly, Mark Carney and the Bank of England Financial Stability Committee are equally concerned. The macro-prudential increase in the countercyclical capital buffer from 0% to 1% to be held by UK banks by November reflects worries regarding both the pace of growth of consumer credit and the quality.

We worry about the low level of savings and potential for a consumption cliff-edge as credit availability dries up along with escalating inflation which we believe will go significantly higher by year-end. The impact of inflation on purchasing power could become quite meaningful and real incomes may be falling as much as 2%-2.5% on an annualised basis by year-end.

None of this represents a strong picture for sterling and, although inflation may provide an argument to raise rates back to 0.5%, the growth picture is decidedly vulnerable. We believe any increase in UK rates is unadvisable and should be incremental if implemented.

In summary

In summary, the macro data inform us that the reflation trade has stalled but is not dead, monetary policy is still very loose, fiscal policy is neutral, and equity valuations are actually still around average levels in the developed markets and cheaper in emerging markets.

Political risks have moderated but so too has some of the credit impulse that kick-started growth in 2016. A policy mistake of raising interest rates too soon in the US is probably the highest risk facing the markets.

When viewed as a combined entity, the EU still surpasses China as the world’s second-largest economy and the good news is that it is improving. Employment and consumption are gathering pace and this will help to maintain some global momentum in the second half of this year.

However, as the lagged effects of the slowdown in credit growth in China and the US start to take effect, a summer lull in global activity is a decent probability. This suggests to us that it will be difficult to repeat the kind of gains in equities that we have seen to date over the next few months.

The lull should be relatively short and shallow, and investors will be in a better position to identify the ripples of a resumption of credit growth and global economic momentum towards the year-end. That said, the outstanding ability of politicians, companies and Central bankers to surprise us, means that we tend to resist market timing.

The challenge investors will face as we move into 2018 is that full employment and the return of the reflation trade would make a strong case for a coordinated monetary tightening that robust earnings growth will need to offset.

For more information on our latest investment views please contact us on 020 7189 2400 or contact@tilney.co.uk

Disclaimer

This article was previously published on Tilney prior to the launch of Evelyn Partners.