While the forthcoming debate will inevitably focus on economic issues, in all probability the outcome will be shaped by the electorate’s more emotional responses to the issues of immigration, border control and security.

Why are we having a referendum?

Confronted by growing Euroscepticism in his previous term as Prime Minister and faced with growing grass roots support for the UK Independence Party, David Cameron pledged that he would announce a referendum on UK membership of the EU if elected to a second term as Prime Minister.

Gambling that he would be able to use his authority as a re-elected Prime Minister to renegotiate key aspects of the UK’s relationship with the EU and thereby quell internal dissention, the PM entered into a round of talks that have generally been regarded as insubstantial. With the Conservative party split by the PM’s negotiating failure and with collective cabinet responsibility suspended for the vote, it is significant that the campaign will effectively be run by two cross-party coalitions.

How is the question being phrased?

In order to avoid any implication of bias, the electoral commission rephrased the referendum question from ‘Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union?’ to ‘Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?’

Responses are to be marked with a single (x): ‘Remain a member of the European Union’ or ‘Leave the European Union’.

Which issues will sit at the centre of the campaign?

Membership fee

Leaving the EU would result in an immediate cost saving to the Treasury. Last year the UK contributed around £13 billion to the EU but received £4.5 billion back through farming subsidies and regional development investment. An additional £1.4 billion is returned as grants to the private sector for a net contribution of £7.1 billion.

Although significant, these numbers will be dwarfed by the impact on the public finances in the longer term from trade.

Trade

The EU is a single market in which no tariffs are imposed on imports and exports between member states. More than 50% of all UK exports go to EU countries. Taking into account the additional benefit of bilateral trade agreements between the EU and other countries that also benefit Britain’s exports, this figure rises to 62%.

An exit from the EU would put unfettered trade access at risk, but remove large swathes of unpopular and restrictive bureaucracy that increases cost and restricts innovation. In addition, Eurosceptics will rightly argue that the vast majority of small and mid-sized business do not directly trade with the EU but remain bound by excessive regulation.

Investment

Inward investment slowed in the run up to the Scottish referendum but bounced back after the outcome of the vote. The protracted negotiation that can be expected to follow an exit vote could mean an investment hiatus for the UK lasting several years.

International companies such as BMW have suggested they may leave the UK in the event of Brexit, while the country’s preeminent status in financial services could be threatened should any of the global banks headquartered in the UK be relocated.

Immigration

Under EU law Britain cannot prevent anyone from a member state coming to live in the country. While Britons benefit from the same right, the result has been a huge increase in immigration into the UK – largely from Eastern Europe. According to the office of national statistics nearly 950,000 Romanians, Bulgarians, Czechs and Poles have entered the country in comparison to less than 800,000 workers from Western Europe.

Security

Hand in hand with concerns over immigration are the growing tensions created by cross border security. Iain Duncan Smith’s support for Brexit has been directly linked to the ‘open door’ policy that allows unfettered access across the UK’s border.

While there is a very significant difference between the arguments for and against those seeking legitimate economic migration or political asylum and the threat posed by terrorist infiltration, the cross contamination of the two issues will be seen as a potential vote winner by the pro exit camp.

So, is anyone winning the argument?

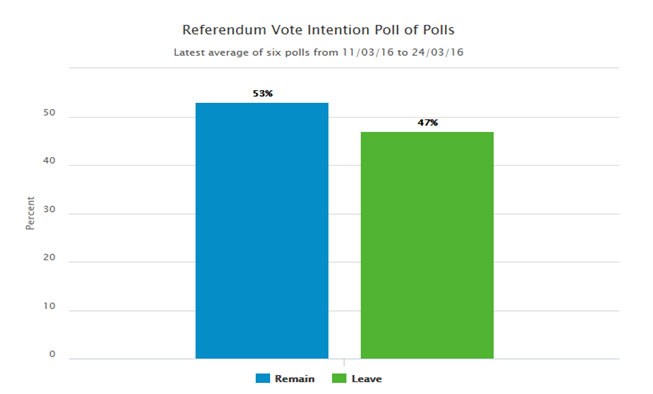

The unequivocal answer from current opinion polls is no. The remain campaign has consistently polled between 50 and 56 % of those expressing a view, but with nearly 20% of respondents remaining undecided and official campaigning not due to start until 15 April, the outcome remains close.

Source: What UK Thinks 15/03/2016

Is this all about the economy?

The uncomfortable truth for both sides is that while the economic implications of Brexit remain the main focus for both campaigns, technical arguments based on a wide range of theoretical outcomes are unlikely to sway the wider electorate. Instead, the polls suggest a population divided on the basis of age, education and geography. Young, educated, middle class and southern voters are the most likely to want to stay within the EU, while those over 55 and from an unskilled or semi-skilled working background are most likely to vote to leave, as the graph below demonstrates.

Source: telegraph.co.uk the vote to remain is more prominent in the first two groups. ‘Social grades’ data taken from 2011 Census: AB is higher and intermediate managerial, administrative, professional occupations; C1 supervisory, clerical & junior managerial, administrative, professional occupations; c2 skilled manual occupations and DE semi-skilled & unskilled manual occupations, unemployed and lowest grade occupations.

This division reflects the cross-party nature of the vote, stripping much of the electorate of its tribal party identity. Instead, faced with complex and imponderable economic arguments, much of debate is likely to devolve to the most emotive issue of all: immigration.

What about immigration?

The EU says that the “freedom of movement and residence for persons in the EU is the cornerstone of Union citizenship”. The emotive but subliminal sub-text of the Brexit campaign will be the coalesced issues of immigration, labour mobility and border sovereignty.

For the year to September 2015, net migration into the UK has been reported at 323,000, three times the Government’s official target. Of this figure, 172,000 are EU citizens permitted under the EU’s freedom of movement principles to enter the UK when seeking employment. With the UK imposing stringent visa requirements on migrants from outside the EU, pro-Brexit campaigners believe current rules favour unskilled European workers over the more highly skilled from elsewhere.

Arguments for and against this supposition will continue throughout the campaign, for while the flood of semi-skilled workers represents an employment threat to many, they have also helped boost consumption (the young and low paid spend, the older and well off save) and keep wage inflation at manageable levels.

However, the perception that a vote for exit will also mean greater control over immigration could be misplaced. Complex negotiations will be required before an exit could be achieved, with compromise over labour mobility one of the bargaining chips that may be used in an attempt to retain access to the European Economic Area (EEA).

How would we leave the EU?

While there is no precedent for a sovereign member state leaving the EU, the procedure for withdrawal was set out under the Treaty of Lisbon (2009). This specified that a member state may notify the European Council of its wish to withdraw and set a maximum two year time frame for the terms to be negotiated. Should the terms of an exit not be concluded within that period, an extension can only be granted with the explicit approval of all remaining member states.

One of the key tenets of the exit campaign is that the EU will need to maintain close economic ties with the UK. Under such an assumption, the terms of the exit negotiations are seen as benign, maintaining UK access to EU markets without the pitfalls associated with the burden of regulation.

While this argument appears reasonable it probably also underestimates the threat a UK exit would pose to the wider EU experiment. It is quite conceivable that, faced with a UK vote to withdraw and mindful of the threat posed by further secessionist factions across the union, withdrawal negotiations would be both protracted and driven by a polemic need to make exit as difficult and painful as possible.

So for all the cogently argued analysis it is simply not possible to know how the exit negotiations will progress, what terms will agreed and what the longer-term economic repercussions may be.

The Financial Times highlighted this point in a recent study that demonstrated how very small changes in the assumptions made about the terms of exit swayed the longer-term economic outcomes very significantly.

What is the Norwegian model?

The most talked about middle ground for a negotiated exit is the so-called ‘Norwegian model’, which would allow the UK to remain within the European Economic Area (EEA) but not the EU. The EEA is a formal trade agreement between the EU and the remaining three members of EFTA (European Free Trade Association) – Norway, Iceland and Lichtenstein. It gives access to the single market but with limited say on rules and regulations. This halfway house could give trade access without the need for full monetary policy integration.

Such a compromise however comes at a price. EU regulations over trade are adopted in full by the Norwegian Government and enforced on all companies whether they trade within the EEA or not. Moreover, in order to meet entry requirement for the EEA, Norway has also enshrined the EU working time directive and the principles of labour mobility in its domestic legislation.

Because unfettered trade is just one of the four economic freedoms (“free movement of goods, services, labour and capital”) that sit at the heart of the Union, the probability that the UK could negotiate unencumbered trade access while abandoning free movement of labour seems unlikely.

Is there a second way?

It therefore seems probable that an exit vote will lead to difficult and increasingly polemic negotiations. With the UK keen to re assert its rights over the key issues of trade, immigration and parliamentary sovereignty, and the EU fighting to preserve the sanctity of its four key freedoms, the path to a compromise agreement would appear difficult.

In addition, the position of David Cameron could become untenable as he is forced to negotiate terms of an exit he fought hard to avoid and whose basic provision he would disagree with. Nearly 50% of voters polled believe the PM should stand down in the event of an exit vote. The risk of a Conservative party leadership contest would therefore seem a likely pre-cursor to entering exit negotiations, raising the risk of a permanent split within the Conservative party and the risk of a more entrenched UK negotiating team.

What do you think the outcome will be?

With the opinion polls giving hope to both sides, the outcome will be determined by the ability of the two campaigns to mobilise their respective support. Here the exit campaigners have a natural advantage. We view the demographic of their support as more easily mobilised than the generally younger remain supporters, who have a lower propensity to vote. Offsetting this is the increasing risk the Brexit camp will mount a disjointed campaign, split between the number of rival factions united in favour of exit, but divided by what an exit could and should mean for the country.

At present there appears a relatively complacent assumption that the combination of a central coordinated campaign led by the Prime Minister, allied to the natural conservatism of the UK electorate, will see the remain campaign prove successful. However, with the recent budget fiasco undermining Cameron’s leadership credibility and the security concerns raised by the Brussels bombings there is a growing possibility of a surprise vote to exit.

On balance we believe the outcome will be a narrow victory for the remain campaign. However the unforeseeable nature of the outcome is unlikely to put the issue to rest once and for all.

What would Brexit mean for the UK economy?

While the consensus continues to believe the outcome of the June vote will be in favour of the remain campaign, the close polls will inevitably give rise to periodic bouts of uncertainty over the outcome. While many commentators have focused on sterling as the most likely casualty throughout this process, weakness during the first two months of the year, allied to the monetary policy measures being pursued elsewhere, suggests these fears may be overdone.

Indeed, it is telling that Boris Johnson’s declaration in favour of Brexit did more to weaken sterling than the ECB’s decision to cuts rates and increase QE weakened the Euro. Good news for the raft of UK based companies doing business overseas, but a salutary lesson for those who believe investment is driven by fundamentals and not sentiment.

While we would expect a short-term hiatus on spending and investment plans ahead of the vote, this would clearly be a blip in the event of a vote to remain. An exit vote however would sustain this period of uncertainty through the two-year negotiating period.

Corporate posturing in recent months suggests that certain UK-based industries could even consider relocating elsewhere in Europe, particularly if the UK was unsuccessful in maintaining membership of the EEA. Motor manufacturers such as BMW have publicly articulated this threat while other global companies have made similar noises (at least in private).

The magnitude of this threat could be determined by the ongoing negotiations between the EU and the US for creating much closer trading ties in the face of predatory pricing pressure from China and Asia. A satisfactory conclusion of these negotiations combined with a tough negotiating stance from either side could have significant longer-term repercussions for economic activity.

How would the Bank of England react?

Estimates of the extent of the economic impact vary significantly, but are generally thought to be in the range of a 0.5 – 2% reduction in GDP in the year after the vote to leave. In this event, we would expect the Bank of England (BOE) under Mark Carney to do whatever is deemed necessary to maintain monetary and financial stability. However talk of an immediate rate cut, or the possible commencement of additional QE, would appear wide of the mark at least initially.

With a lot resting on the stability of sterling, the BOE will in all probability focus on credit easing measures to boost activity to avoid undermining the currency. In combination with supplying additional liquidity to the banking system, the BOE will hope to provide sufficient reassurance without recourse to additional monetary stimulus.

In the medium term however, exit will pose a policy dilemma for the BOE. Weaker growth and declining FX rates will create potentially equal and opposite inflationary pressures requiring a policy balancing act. However, the relatively dovish positioning of the world’s other major Central banks gives scope for rate cuts or more Quantitative Easing (QE) should the uncertainty over negotiations become protracted.

What about the future of the EU?

To global investors the impact of Brexit is most keenly seen in worries over the sanctity of the EU, for although the UK is not part of the single currency its secession would be of far greater consequence than earlier worries over Greece. These concerns are based on two key facts:

- The UK is the second largest EU economy after Germany

- A UK exit would be the voluntary secession of a robust economic entity rather than a forced expulsion of a non-compliant economy

In the event of exit, the negotiations would clearly be seen as creating the blue print for other countries to pursue the same model for possible withdrawal. With growing anti-EU feeling in Spain, Italy and France, the greatest risk to the UK in an exit vote may actually be the subsequent disruption it will cause more generally across the EU.

Secessionist factions across the EU will take heart from the close nature of the UK campaign and will, in all likelihood, gain support the longer the region’s economies remain weak and policy responses uncoordinated. The loss of trade associated with a UK exit, even if temporary, could be enough to tip the region back into recession – putting yet more pressure on Mario Draghi and the ECB.

What else should we be thinking about?

Any outcome threatens Britain’s political status quo

While the majority of the arguments ahead of the vote focus on the risks associated with the outcome, we would argue that the process itself is probably the biggest short-term threat faced by the UK. While the Conservative party appears most at risk of an internal schism, rifts are also appearing within the Labour party. Many rank and file members are at odds with the party’s pro-European stance, finding themselves most aligned with the vote to leave. Moreover, the ambivalent position adopted by Jeremy Corbyn is only helping widen the divide at the top of Labour.

While a vote to remain may allow both parties to retain some semblance of internal harmony, the closeness of the vote and the cross-party nature of the issue suggest that internal disharmony within both parties will take time to heal. Should an exit vote be accompanied by a renewed SNP campaign for Scottish independence, we could be about to witness the greatest shift in the political landscape in Britain since the rise of the Labour in the inter-war years.

Conclusions

Economists are notoriously incapable of forecasting the path of future growth even when operating in a steady-state environment of known rules and reasonably clear policy. Making bold claims about the long-term risks or benefits of Brexit, when the terms of any exit are at present unknowable, smacks of little more than self-serving rhetoric. We would therefore discount many of the more sensationalist claims emanating from either camp, preferring to focus on what we know or can reasonably expect to happen. These are our key thoughts:

- We continue to believe that come June, the UK will vote to remain within the EU

Despite the closeness of the current polls, the fear of change and the relative uncertainty over the path an exit might take will likely sway voters in favour of the remain campaign

- Despite sterling weakness stock markets are generally assuming this outcome

A deterioration in the standing of the remain campaign in the polls leading up to the vote will therefore negatively impact asset prices – most notably Eurozone equity

- While short-term domestic economic activity will be impacted, the outlook for the UK stock market is less clear cut

With over 60% of FTSE 100 earnings generated outside the UK, the translation benefits of a weaker sterling would represent a temporary boost to corporate earnings, helping to support dividends and even share buy backs

- There is much more at stake for both the EU and the UK than many currently believe

For the UK, a vote to exit could re-shape its political landscape, breaking down the established party structures that have endured since the first quarter of the 20th Century.

For the EU, losing the UK will create far greater tensions than fears of Grexit in 2011. Secessionist factions across much of Europe will be emboldened by a vote to leave, while the terms negotiated for any UK exit will be viewed as a route plan.

Disclaimer

This article was previously published on Tilney prior to the launch of Evelyn Partners.