It may seem more difficult to make good profits from livestock. With subsidies under pressure, farmers can take measures to enhance the resilience of their business.

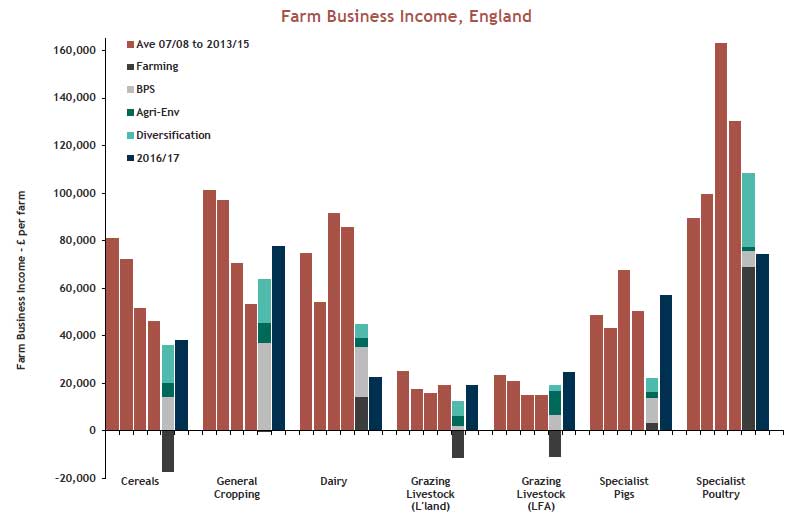

Farm Business Income (FBI), or profit for ‘average’ farms in a particular sector*, can be used to compare performance between farming sectors.

An analysis of FBI in England over eight years shows that it is more difficult to make good profits from beef or sheep farming than other sectors.

This suggests that profitability is low, not solely because of the location, but because the choice of enterprises available to the farmers is limited in these regions.

FBI in 2015/16 is divided into four components of farm business. The red bar is the profit from farming itself. It is clear that, for grazing livestock, this is negative for the average farm and that other incomes are required to generate profit. It is also clear that the sector is reliant on subsidies to turn a profit

and that there is no money from being ‘average’ in livestock farming any more.

The ‘average’ grazing livestock farmer also makes less profit than an average performer of any other farming sector, most years at less than £20,000. Perhaps counterintuitively, the data also demonstrates that the income in less favoured areas is no better or worse than grazing livestock in the lowlands.

Many prophets of the agricultural implications of Brexit suggest that agricultural subsidies are unlikely to increase when we are no longer subject to the Common Agricultural Policy. Most actually agree that the total subsities are more likely to fall, and that the allocation of subsidy might change from a land-based payment to some other form of support. If true, then farms that depend on subsidy for their survival will have to stop and think. Would your farm be profitable without subsidies (BPS and rural development incomes); or even if it was halved? It is timely for all farmers to consider their future to ensure that businesses are robust enough to face a range of scenarios.

It would also be prudent for farmers at this point to explore what changes they might be able to make to strengthen their farm business if Brexit leaves them financially exposed.

The remarkable resilience that farming in the UK demonstrates is, however, worthy of note. Historically, few farms have gone out of business when prices have been low, one way or another, most continue to operate. The rate at which farming numbers have changed in the last 20 years is slow compared with most other business sectors. This is testament to the dedication, determination, and commitment of the farming community, but also to the subsidy received.

Lessons from a ‘model farm’

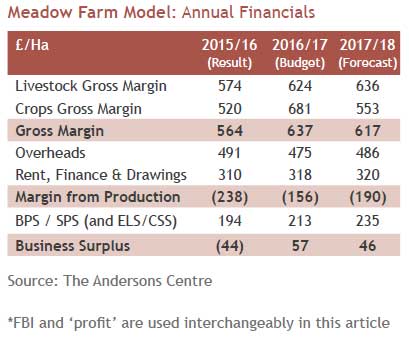

The Andersons Centre has a grazing livestock farm model called Meadow Farm. It is a notional 154 hectare (380 acre) lowland mixed beef and sheep business typical of many family-run livestock operations across Great Britain. The farm has a 60- cow suckler herd and a 500-ewe mule sheep flock; in both cases finishing all progeny. There is also a small dairy-cross bull-beef enterprise and some cereals. The model provides an accurate representation of business structures and changes in annual performance.

The gross margins are insufficient to cover the overheads, rent, finance and drawings so losses are made before subsidy. Like many similar businesses, the overhead structure of Meadow Farm is too large for the output the business achieves. The agri- environment scheme (ELS) finished part way through 2015/16 and a new Countryside Stewardship (CSS) agreement is expected to start next year. Over the long term, it is questionable whether Meadow Farm, in its current format is sustainable for the future, and changes are needed to improve it.

The key message from this table is that, each year, this farm is losing a lot of money before subsidy is accounted for. There are quite a lot of small-medium sized farms like this in Britain; some will be making a reliable profit, but many others will not.

Adding value and differentiating products, finding new outlets for produce (e.g. farm shops, local markets and high end or specialist retailers) and selling the background story can increase profitability, however this can be challenging to scale up.

Many are looking at low, long term fixed interest rates available to farmers and landowners, together with diversification opportunities and perhaps making use of permitted development rights opportunities in order to use the farming assets to invest to provide additional future sources of income. These may

be invaluable over the coming years, at times of instability and economic uncertainty. Future farming losses might at least be relieved against income from other sources, further helping to support the business as a whole.

DISCLAIMER

By necessity, this briefing can only provide a short overview and it is essential to seek professional advice before applying the contents of this article. This briefing does not constitute advice nor a recommendation relating to the acquisition or disposal of investments. No responsibility can be taken for any loss arising from action taken or refrained from on the basis of this publication. Details correct at time of writing.

Disclaimer

This article was previously published on Smith & Williamson prior to the launch of Evelyn Partners.